Pēteris Strautiņš, Luminor economist

Autumn 2020: Global economy predictions

Pēteris Strautiņš, Luminor economist

It was broadly predicted that the recession caused by COVID-19 will be the deepest economic crisis since the Great Depression, considerably surpassing the Great Recession experienced in 2008-2009. Such scenario is still possible, yet the latest economic data show that the global economic decline in 2020 will not be as substantial as expected. Firstly, the COVID-19 pandemic is becoming less lethal and, therefore, even the countries that are repeatedly experiencing an increase in the number of COVID-19 cases are not in a rush to renew nationwide movement restrictions or other restrictive measures. As a result, even if the “second wave” of the COVID-19 pandemic starts in autumn/winter, the adverse economic effect would be much smaller owing to the change in reaction of governments and households. Secondly, the implemented unprecedented fiscal stimulus measures during the peak of the pandemic have kept economies afloat. Generous allowances for idle time helped retain low unemployment level, the liquidity support provided to businesses prevented mass bankruptcies of companies, in turn household income support measures in many countries enabled swift recovery of private consumption as soon as restrictions on movement were eased. It is still not clear how these measures will impact long-term economic growth, considering the crippled economic stimuli and the record-high rise in national debt levels, yet it is becoming more and more clear that in many developed countries, fiscal stimulus measures have helped to prevent the deepest economic crisis or at least hold it over for more distant future.

Epidemics come and go while economic stimuli stay, so there is a very high chance that in 2021, we will witness a strong economic recovery process promoted by fiscal and monetary policy matching up to seriousness of the situation, as well as allayed fear of COVID‑19. The Federal Reserve System (FED) recently announced about changes in its inflation promotion regime, leading to understanding that the rates might get stuck at the zero mark even up to 2025. Such situation will in turn make ECB and other major central banks to retain interest rates at zero level or close to that for many years to come. Fiscal policy will most likely retain the ability to adapt as well, especially in EU member states, since a 750 billion euro Recovery Fund has been agreed upon. Considering these measures, we must not disregard the risks of potential overheating of economy and asset price bubbles forming after the COVID‑19 crisis ends. Especially keeping in mind that similar processes could also be observed in Hong Kong in 2003 after successful restriction of the SARS pandemic.

However, not everyone is taking part in writing a success story because the recession caused by COVID‑19 is unique in the fact that it has unequal impact on different countries, segments of economy, social groups and asset categories. That is why the global economy recovery process will more likely take a “K shape” (uneven recovery with increasing regional differences), rather than “V shape” (rapid and short recession followed by swift recovery), “U shape” (rapid and longer recession followed by gradual but fast recovery), or “L shape” (rapid recession followed by very slow and gradual recovery).

“K shaped” global recovery reflects big regional differences. Southern Europe, Latin America and India experienced a particularly strong blow of the COVID‑19 recession, and their recovery is slow, largely according to the “L shape” scenario. Whereas Northern Europe, Far East and Australasian regions were the least impacted by the pandemic, as they are experiencing recovery in a “V shape” or even “J shape” (short recession followed by economic upturn), and some countries have even managed to completely avoid recession according to its “technical” definition. In turn Western Europe and North America are between the aforementioned models, mainly following the “U shape” scenario. Hence, contrary to the dominant opinion, the recession caused by COVID‑19 has uneven impact on different countries, thus increasing global economic differences.

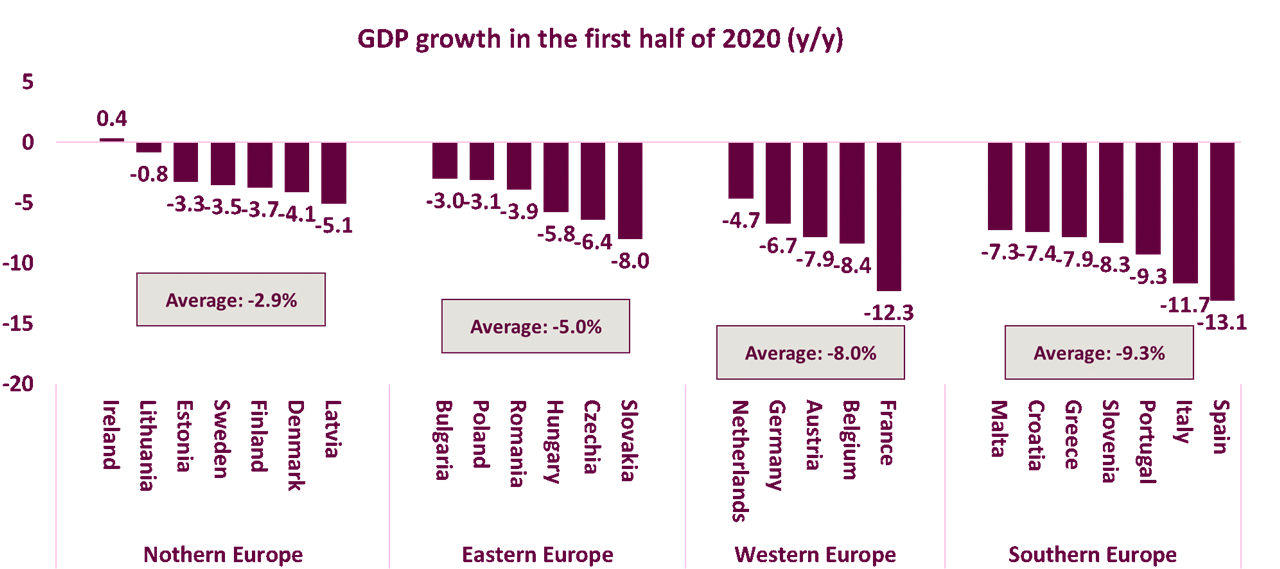

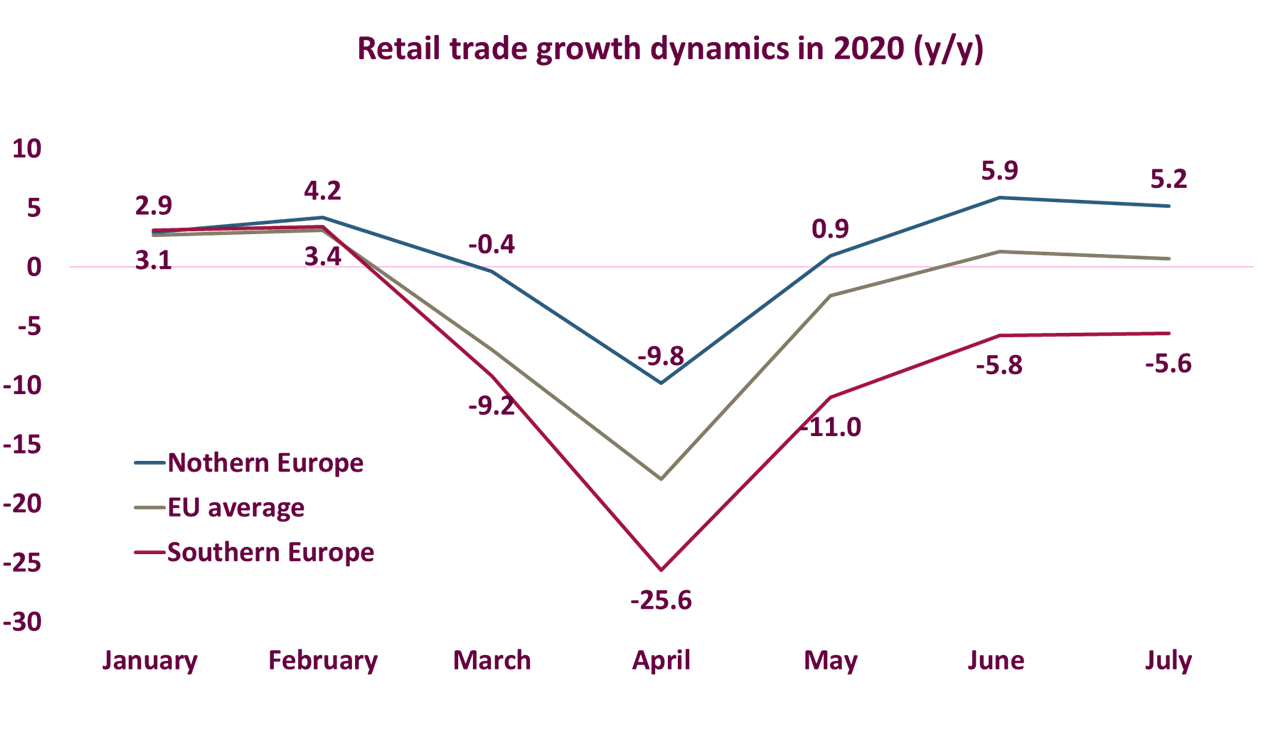

The “K shaped” or variable-speed recovery scenario in the EU territory is becoming comprehensive, creating an even bigger gap between the Northern and Southern regions. When presenting economic predictions back in spring, the European Commission anticipated a rather even recession throughout the EU; It was forecast that the difference between the highest (-9.7%) and lowest (-4.3%) fall in GDP will be rather small (5.4 percentage points). In turn, in economic predictions made in the summer, this difference has grown (to 6.6 percentage points), and the latest data show that it will no doubt need to be increased even more. For example, the EU member states with the most severe recession in the second quarter of 2020 (Spain, France, Italy, Portugal and Greece) experienced a 15-22% fall in GDP, while the GDP decline in member states with the best results (Ireland, Lithuania, Finland, Estonia and Sweden) was only 3-7%. The latest data show that the gap between the Northern and Southern regions will remain because the Southern Europe countries that are dependent on tourism and burdened by substantial debts are unable to activate their economy, while the Southern European countries are already experiencing a comprehensive economic recovery.

For example, increase in retail trade volumes in July in Italy, Spain, Portugal, Croatia, Slovenia, Malta and Bulgaria was still below the previous year’s level, while in most of Northern European countries this index has been in pre-crisis level already since May or June. Therefore, the European Union is (again) experiencing a variable-speed recovery, observing a “V shaped” recovery in Northern European countries, a “U shaped” recovery — in Western European countries, and an “L shaped” recovery in Southern European countries. The current risk is that the gaps between the Northern and Southern regions may worsen political tensions, especially in autumn, in the process of budget planning for 2021.

“K shaped” recovery is stimulated by unprecedented changes in industries. Experience shows that economic recovery processes are often compared to performance during the pre-crisis periods. However, it should not be that way this time, as COVID‑19 recession has completely changed the behaviour of consumers and entrepreneurs alike. As a result, economy in the periods following COVID‑19 pandemic will be different from the pre-pandemic economy, or as the saying goes, „you cannot step into the same river twice”. Namely, some segments of economy will never recover to pre-crisis level due to their structural changes that where sped up by the pandemic. The most noticeable ones of such changes is teleworking and e-commerce, which will completely change the role and functioning of IT, real estate, trade, transport, travel, production and other sectors. The countries that will be the fastest to adapt to these changes will be the fastest to recover from the COVID‑19 crisis. On the other hand, countries falling behind from others will find it difficult to achieve growth in the world post COVID‑19. In this context, North American, Northern European and Far East countries have competition advantages in relation to other regions of the world, so there is a high chance that the COVID‑19 pandemic will expand the global economic differences.

There is a risk that a “K shaped” economic recovery will worsen income inequality in countries. Economy sectors where the most generous salaries used to be paid before the COVID‑19 recession (IT, finance, public sector) have suffered comparatively less than the sectors where lower salaries were paid (recreation, travel, catering and other services), which is why it is likely that income inequality will increase. Furthermore, the recent boom in stock markets (and the anticipated boom in real estate market?) facilitated by unprecedented fiscal and monetary stimuli will most likely increase the well-being inequality. The growing inequality in income and well-being may force governments to increase taxes and/or public expenditure (e.g., implement a universal basic income), which might constantly expand the role of governments in economics.

“K shaped” recovery can be observed also in financial markets, with share prices deviating from commodity prices. During the economic recovery after the crisis of 2009, oil and metal prices increased faster than share prices, thereby enabling Russia and other countries exporting goods to achieve fast economic recovery. This time, the situation is completely opposite. The global stock market index has already reached the pre-crisis level, while commodity indexes are failing to get a positive impulse. It is expected that these tendencies will continue, considering the changed economic structure, global trade decline and the broad plans of the EU to reduce CO2 emissions (after all, the stone age ended not because of lack of stones), which is why economic differences between the European Union and Russia will continue growing.

“K shaped” variable speed recovery of Europe

Gap between Northern and Southern regions of Europe

The Baltic economies have joined the Northern Europe Union

In 2017, the United Nations Organisation classified the Baltic States as countries of the Northern Europe. Three years later, the Baltic States proved that they have justifiably earned this status, demonstrating Nordic style ability to adapt to the recession caused by COVID‑19. And indeed, economies of the Baltic States alongside economies of other Northern European countries were among the least affected by the pandemic in the EU territory. In the first half-year, the EU economy experienced a fall of 8.3%, yet the economic performance of the Northern European countries was considerably better, experiencing only a 2.9% decline, in turn the Baltic States — only a 3.1% decline. For that reason, contrary to the economic crisis of 2008-2009 when economy of the Baltic States was among the most severely affected in the EU, this time the economic recession level will be among the lowest in the EU.

The ability of the Baltic states to adapt has resulted in effective management of the COVID‑19 health crisis and non-existence of internal and external imbalance during the pre-crisis period. The Baltic States ranked among top five in the OECD index published in May, which evaluates how effectively countries have reacted to COVID‑19. The comparatively low number of COVID‑19 cases allowed to gradually soften the introduced quarantine measures already from mid-April, which in turn enabled economic activity to recover faster than in the rest of the EU territory. The Baltic States were also the first ones in the EU territory to open mutual borders (the Baltic States travel bubble) already in middle of May. As a result, majority of companies had fully resumed activity in May already, substantially scaling back the overall economic decline in the second quarter of 2020.

After the global economic crisis of 2008‑2009, the Baltic States have implemented substantial corrections of external and internal imbalance, resulting in the Baltic States being better at adapting to any external or internal adverse impacts. Furthermore, the economic structure has changed, with rapid growth in volumes of high added value services and high technology production (technical equipment, electronics, chemicals and pharmacy), and export taking an increasing part of the joint export volumes. At the same time, after the economic crisis of Russia in 2014‑2015, businesses in the Baltic States were motivated to strengthen their positions in the Scandinavian and Western Europe markets, hence considerably reducing dependence on Russia and other CIS countries. Lastly, implementation of strict macroeconomic management policies helped to avoid formation of real estate price bubbles, thus improving the ability to adapt to the recession caused by COVID‑19.

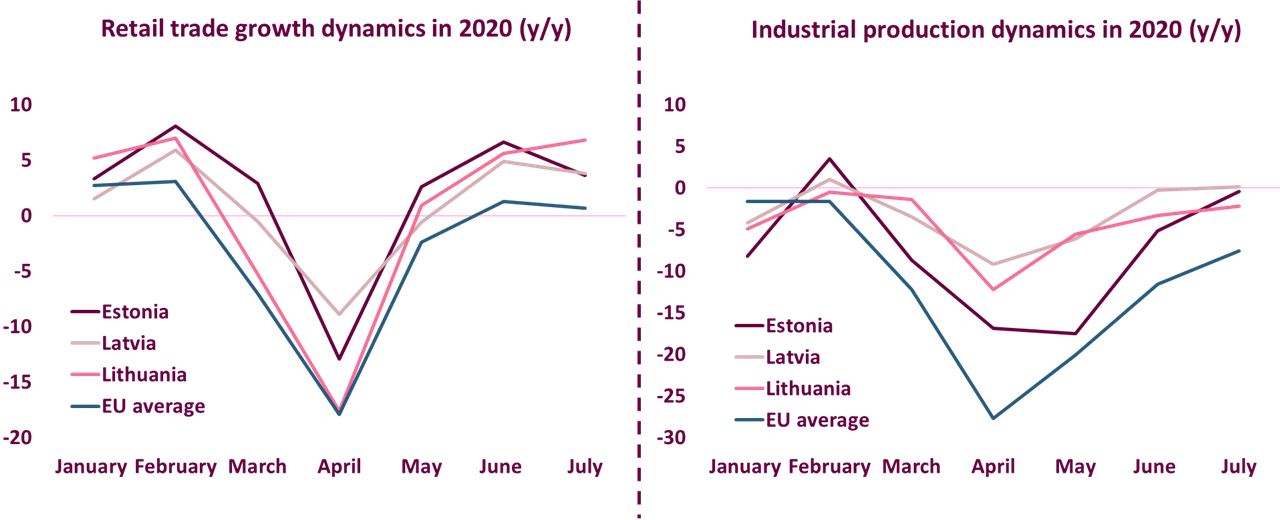

The latest data show that economic recovery in all three Baltic States is in full swing and resembles “V shaped” economic recovery, i.e., rapid but short recession followed by stable and balanced recovery. Retail trade results are especially strong, being well above the last year’s level. That can really be called “Z shaped” or Christmas shape recovery because retail trade activity in the summer resembled the results before the Christmas peak period. Apparently, this economic recovery is partly attributable to release of latent demand because people could not or did not want to make planned purchases during the country’s restrictions on movement, yet it must be taken into account that the total retail trade turnover of the Baltic States in the first seven months of the year (January-July) already exceeds the last year’s results (by ~1‑2%). Industrial production is lagging to a certain extent, but this industry is also gradually recovering and has almost reached pre-crisis performance. Considering that the situation is comparatively good for the main export partners (Scandinavian countries, Germany and Poland), it can be expected that industrial production will reach pre-crisis results already in autumn.

We predict that economies of the Baltic States will continue a strong “V shaped” recovery, with Lithuania and Estonia achieving positive growth in 2020 overall. Therefore, the COVID‑19 recession is heavy, yet it is also the shortest one in history of the Baltic States. In 2021, economy of the Baltic States will strongly push forward owing to economy warming measures, inflow of EU funds and the waning fear of the COVID‑19 pandemic, keeping the growth level within 4‑5%. Contrary to the crisis of 1999 or 2009, this time the Baltic States will have much better results than the EU on average, hence the per capita GDP of the Baltic States (by the PPP parameter) will be close to 80‑90% of the average level of EU and will become similar to the results of Spain or Italy.

The open and small economies of the Baltic States are still subject to risks that might negatively impact steadiness of EU recovery. The greatest risk by far is uneven, variable-speed “K shaped” recovery, which might widen the economical and political gap between the Northern and Southern regions of Europe. We also must not ignore the increasing threat of the “second wave” of the COVID‑19 pandemic. Although there is a slight possibility that nationwide quarantine will be reintroduced in the Eastern European countries, there still is a risk that the Southern European (or even some Western European) countries might reintroduce separate restrictive measures in case the pandemic situation keeps growing worse. Furthermore, such sectors as international travel or aviation sector will feel the drop caused by the pandemic for a while (please see the Annex, which outlines our opinion about the future course of the pandemic). Local challenges still include high unemployment level and uneven recovery of sectors, which might take several years to resolve. At the same time, great opportunities will be provided by a record-size inflow of EU funds, which, if invested wisely, can make economies more digital and greener.

“V shaped” economic recovery in the Baltic States

GDP forecast table (annual change,%)

GDP forecast table (annual change,%)

|

2018 |

2019 |

2020 |

2021 |

2022 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Estonia |

4.8 |

4.3 |

-4.6 |

4.2 |

4.1 |

|

Latvia |

4.3 |

2.2 |

-4.8 |

4.4 |

5.9 |

|

Lithuania |

3.6 |

3.9 |

0.2 |

4.4 |

4.2 |

Annex: Our opinion about the future course of the pandemic

We are not virologists, however, we need to explain our assumptions about the pandemic, otherwise the story of our economy will be incomplete.

Bill Gates who made a clairvoyant prediction about the risk of pandemic says that the pandemic will be over by the end of 2021. That seems credible. From an economic standpoint, the most important question is not “When will the pandemic end” but rather — when will it cease to be a major obstacle for economic activity in systemically important countries. That might happen a long time after the virus is eradicated (it is possible that the virus will not be eradicated at all, and we will have to learn to live with it). This year, several unpleasant surprises were experienced, as well as some pleasant ones. One of them is development of a vaccine, which is taking place much faster than experts predicted in beginning of the pandemic. It is possible that several technologically different vaccines will be available.

We expect that mass vaccination will start around the turn of the year, but it will be a while until it is received by everyone who wants it due to limitations in vaccine production. Health care specialists also warn that no vaccine will be a “perfect” solution — none of them will fully protect completely everyone who gets it and/or will not provide permanent protection, and a part of people will forego the vaccine. However, a perfect vaccine is not what is needed to save the global economy. What is necessary is just for the people who do use it — repeatedly, if necessary, to have enough certainty about ability to resume normal life again. Even if the vaccine does not prevent the disease but only its heaviest forms, that will already be a substantial gain. Any vaccine will serve as only one of the risk reduction measures, along with better medication and better developed social distancing measures. This circumstance brings hope that during the next tourism season, the situation will gradually normalise in this sector, although the negative impact probably will still be noticeable in the upcoming spring season.

We assume that the “second wave” of the pandemic will continue in Europe this autumn, and it will still be accompanied by socialising and travelling restrictions. These restrictions will not be as drastic as the ones experienced in spring of 2020, we do not expect freezing of industrial production, closing of retail trade of non-food consumer goods or restrictions regarding leaving home. For that reason, export of the Baltic States to these countries will not be substantially affected, except the tourism sector, which is at a very low point after all. The first wave of pandemic experienced in March was a huge blow, which halted international tourism, rapidly reduced the industrially produced volumes, affecting both the production and sale process.