Key highlights

- GDP growth accelerated in 2018 despite a universal consensus that the opposite will happen.

- Seasonally adjusted annual GDP growth in Q4, 2018 was the fastest in EU, at 5.6%.

- According to Luminor calculations, Latvia’s GDP per capita at purchasing power parity (69% of EU-28) exceeded that of Greece (68%) in 2018. This is the first EU-15 country we have surpassed.

- Everything is going in the right direction in the labour market – unemployment, employment, labour market participation ratio.

- At the same time core inflation has been amazingly stable for a couple of years at 2%, suggesting that the economy still has unused capacity.

- Net migration balance rapidly moved towards zero in 2018, labour immigration jumped.

- Strong performance is building momentum in consumption and investment that has a chance to withstand the effect of export market fluctuations.

- Structural change proceeds at a healthy pace. The share of high value added services (IT, communications, business services), and manufacturing (machinery, chemicals) in the economy moves up.

- Bank lending is turning around. Both business and household portfolios started to increase in 2018.

- The main question for the forecast period – will the growth momentum hit the wall of labour availability or will employment ratio continue to rise and/or migration will turn around?

It would be very hard to do better than in 2018

GDP growth accelerated last year to 4.8% from 4.6% in 2017 that was already an excellent result. The country enjoyed a fortunate confluence of growth-boosting events. Double-digit investment growth brought by peaking EU fund flows coincided with favourable export markets.

Not only was the overall growth strong, economy performed well on several points:

- Structural transformation. The share of sectors that both create more value added per worker and possess stronger growth prospects is rising — IT and business service exports, certain manufacturing sectors, especially machinery. Productivity is growing in traditional sectors like timber processing through capital deepening.

- Internal and external balances. Inflation was stable in 2018 and is likely to remain such in 2019. Core inflation has fluctuated around 2% since late 2016. Current account balance was slightly in the red (-1.0% of GDP), but it was more than covered by FDI inflows (2.5% of GDP). Consumption is rising, but cautiously, it lags behind income growth as households increase financial buffers against short term income fluctuations and for the retirement.

- Balance sheets. Net external debt, a rarely reported, but important indicator continued the downward path, declining from 24.5% at the end of 2017 to 22.7% last year. This is a reflection of strong savings growth and weak lending, so comes at a cost of by-passed current growth opportunities, but improves financial strength and favours rising investment in the future.

In late 2018 export markets cooled down significantly and are unlikely to bounce back sharply though fears of immediate recession started to dissipate in February.

Growth will slow down, but gradually

Consensus view is probably correct about the overall growth slowdown in 2018-2020 period, but wrong about timing. Average forecast assumes that almost all of this will happen in 2019. We predict that the deceleration will be more evenly split between 2019 and 2020. So GDP growth in 2019 will slow by a percentage point to 3.8%. We switch back to the forecast that was downgraded in Q4 when global business cycle indicators nosedived.

While our GDP forecast for 2019 is relatively optimistic, we do not close our eyes to risks, we see a sharp slowdown in some areas and continued contraction in financial services.

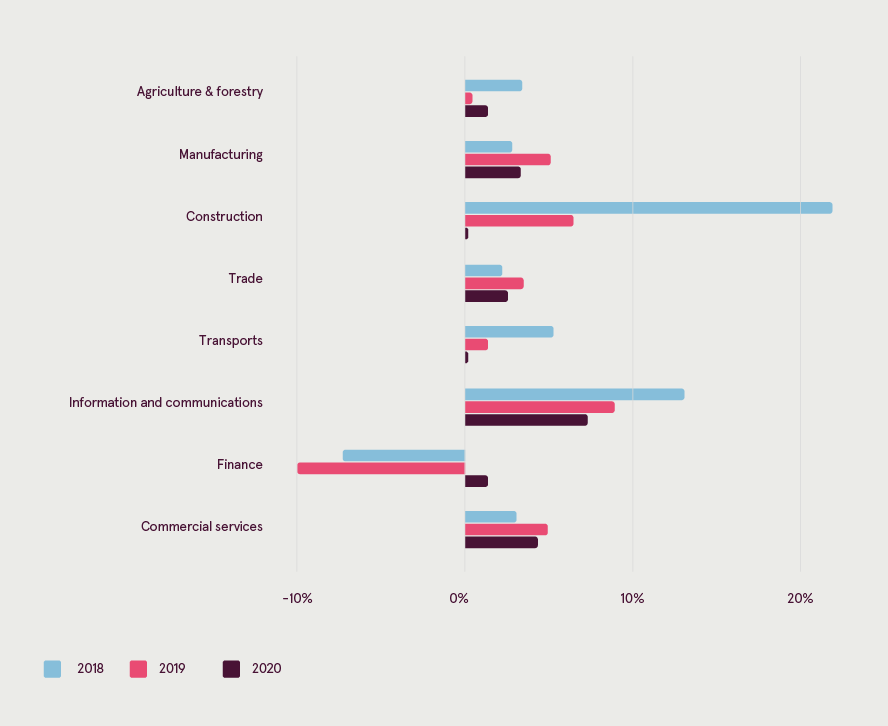

Value added growth in key sectors 2018-2020, fact and forecast

Source: Statistics Latvia data, Luminor forecasts

While the risks of EU fund flow tapering have been exaggerated, these definitely can slow down expansion. We predict that investment growth will be positive in the forecast period, but just above zero in 2020. Building construction will remain quite strong, pulled ahead mostly by rising demand for housing. Building permit data signal intentions to add substantial new office and industrial space. Outlook for infrastructure investment is less favourable. Road construction financing after 2019 is highly uncertain, large port and powerline projects are at or near completion.

Overall expansion will be mostly sustained by consumption as a follow-up of rapid wage growth (8.4%) and employment growth (1.6%) in 2018. For 2020 prospects are more uncertain, but still good.

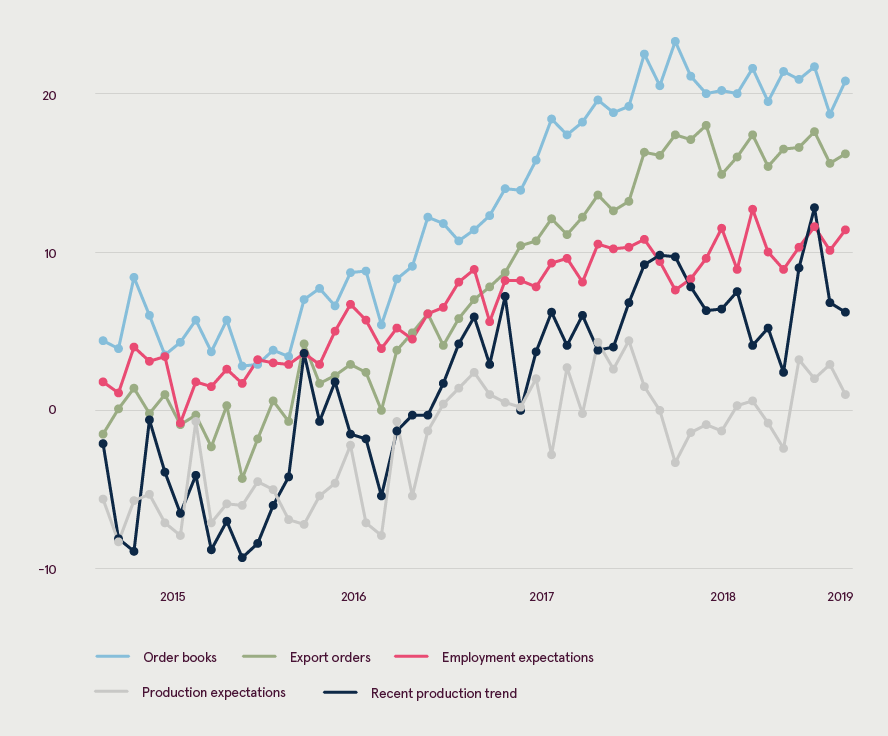

While it is self-evidently true that sustainable growth largely depends on exports, moments of global weakness do not doom Latvian economy to crisis. Past experience shows that Latvian export dynamics are not tightly correlated to business cycle in EU, the main market. Growth rate in other Baltics, industry specific developments can be very important. While a lot of attention has been paid to negative surprises in global trade data, declining confidence indicators in euro area, the most direct evidence about likely production trends — industry survey results from Latvia tend to be disregarded. The forward looking indicators are quite strong.

Industry confidence sub-indices vs their historic averages, points

Source: European Commission data, Luminor calculations

Any macro projections beyond 2020 are very uncertain. In 2021 and following years a lot will depend on the timing of RailBaltica construction. The macro effects of this enormous project can easily swamp all other drivers. It is also important to see how the interaction of the labour market and structural developments will play out.

Labour market pressure cooker will accelerate productivity growth

Unless global economy goes through a very strong upward or downward swing, the medium term future of Latvian economy mostly depends on the labour market. It is both a hope and a worry. It may slow down expansion if companies hit a hard wall in their attempts to increase the number of employees. This is a possibility, but not the only scenario. Media coverage is mostly based on the views of those who see the problematic aspect of recent trends. There are also others. Labour market tightness can drive three positive feedback cycles:

- Increasing labour costs incentivise companies to invest to reduce costs, to increase volume per worker and to increase pricing power through better marketing.

- Increasing attractiveness of the labour market for employees will increase labour supply both through internal and external migration.

- Raising wages will make an increasing share of employees creditworthy, thus driving housing demand. Many will sell or rent their current premises to internal and external migrants that cannot yet afford new homes, increasing the depth of the labour market in growing areas.

Recent developments are favourable. Employment grew by 1.6% in 2018. Gross wages increased at the fastest pace since 2008 — by 8.4%. Also the real net wage growth was strong, at 7.2%, helped by moderate inflation and tax cuts. Wage growth is predicted to slow by about a percentage point in both 2019 and 2020, but the direction of change is especially uncertain in this area.

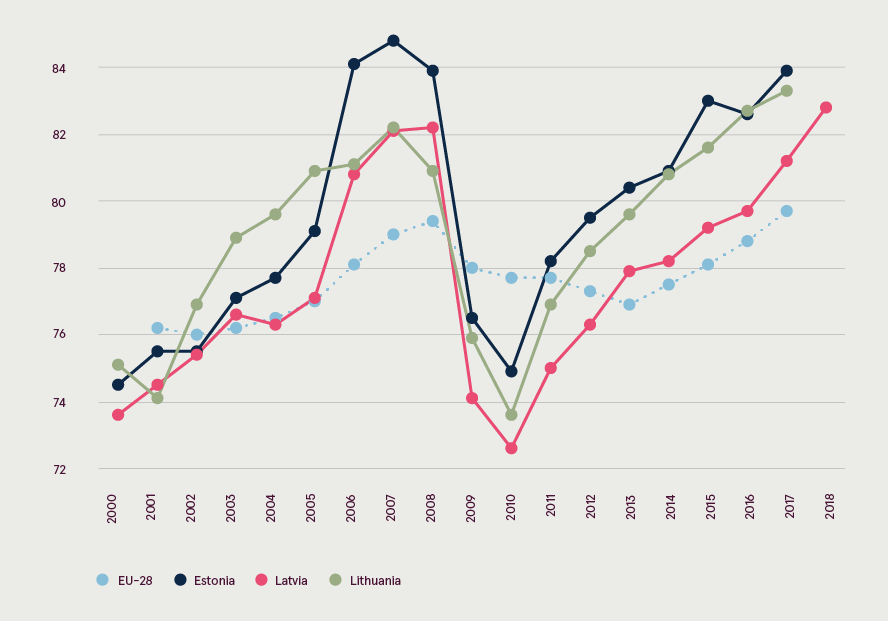

While the employment ratio is rising, Latvian indicator still lags roughly five percentage points behind the Estonian one. By closing it, Latvian economy would get 40-50 thousand extra workers. Unlike Lithuania, Latvia lags behind also in prime working age (25-54 year olds) employment ratio that points to insufficient geographic labour mobility.

Employment ratios in prime working age (25-54 year olds)

So it doesn’t surprise that there are still large rural areas with very low incomes, where the median gross wage is around 500 euros or even below, questioning the need for large scale labour immigration – there is surplus labour in the countryside that can be employed in cities with labour shortage.

Banking sector will continue to change

In 2018 Latvian banking sector changed profoundly. As financial service export activity is reduced, sector will continue to shrink as the share of the economy in the forecast period. In the long run financial service exports from Latvia probably will grow again, but these will be very different from the past, based on financial technologies in which Latvia and other Baltic states are quite strong.

Also those banks that mostly serve local businesses and residents go through a period of rapid change, driven by changes in technology and consumer habits. As the provision of financial services takes up a declining share overall working time in the economy, the share of the sector in GDP will probably continue to shrink. It is a sign of success, not failure. Banks should function so well that they are almost unnoticeable. This is not a part of the economy that drives growth by itself; it serves other parts of the economy that do.

There are indeed also growth areas in the sector. Savings will rise faster than income in the future as people take on an increasing share of responsibility for pension provision and increasing affluence increases the capacity of households to reduce old age and other financial risks. Increasing savings is one aspect of increasing financial intermediation, the other is lending. Ratio of total household and business loans to GDP is still a fraction of that in a typical rich country. This gap will close, but gradually.

Things to do

- Creating favourable conditions for knowledge-based economy is the most important work that state can accomplish for building future prosperity. Unfortunately, this is a public policy area where Latvia underperforms like in no other. Our innovation metrics are at or near the bottom in the EU. The main reason is painfully obvious – low financing of science and R&D. There is only one realistic way to address the problem — consolidate the school network. Latvia’s combined education spending is the highest in EU as a share of state budget.

- It is very important for businesses to understand that labour market has changed permanently. There has been a big labour surplus in most of post-soviet era, it will not come back. Any changes to immigration policy will only partly alleviate pressure to raise the value added per employee. Many enterprises that fail to raise productivity will close.

- Government is right to promise a stability of the tax system after recent profound reforms. There is a room for technical improvements that do not cause harmful uncertainty for business, for example, simplifying the income tax progressivity.

- While the share of manufacturing in the total value added has failed to move towards 20% as inscribed in the National Development Plan, the sector has proven its value as a growth driver in regional cities. Government and municipalities should make sure that decision making about the availability of production locations is fast and transparent. Subsidies to investment in industrial premises could be appropriate in areas with limited supply and prospects of market driven improvement.

- New regulation of rental housing is of enormous importance for housing investment, labour mobility, and preservation of architectural heritage thus also tourism, quality of life and economic growth in general.