This is the most confusing time for writing about global economic prospects. As we finish these sentences, the world is moving into unfamiliar territory and might move much deeper there by the time of publication. Many decades have passed since inhabitants of rich countries last faced a realistic prospect of contracting a disease as dangerous as COVID-19. The risks are high enough to affect people’s behavior and that is indeed changing. So the economy is changing too, rapidly. Modern economy depends on travel and human interaction that is being restricted. Economic impact comes from the immediate impact on demand (especially for travel, catering and entertainment), lost output due to absence, also disrupted value chains. Postponed investment, consequences of financial market overreactions, impaired balance sheets will follow.

The new coronavirus is not the only thing that matters to economic prospects, but currently it overwhelms all other short-term drivers. There have been other interesting developments since our previous report and sometimes in the future other forces will take over. However, first we have to deal with this extraordinary situation. Hedge fund guru Roy Dalio has called it “once in a century disaster”, we hope that he is wrong, but strong words can be useful by focusing attention.

The economic impact of the epidemic is only emerging. One can classify it into the following components:

- Direct impact on global GDP from lost output in China, that is still the place of the majority of cases reported so far (until March 9). The country equals 16.2% of the world economy at market exchange rates and 19.2% at purchasing power parity (IMF estimates for 2019). It is home to ~30% of global manufacturing. We believe that estimates of 2% loss of output in 2020, in other words ~4% growth instead of ~6% roughly indicate the scale of the problem. That alone would deduct ~0.3% from the global economy. The notable success of epidemic control in China has been achieved through “freezing” much of economic activity for a while.

- Disruptions of supply chains. China is an enormously important supplier of components. For example, it provides ~400bn worth of electronic components. Without supplies from China much or even most of global manufacturing would eventually grind to a halt. This threat is receding, fortunately. There are also promising signs in South Korea another important manufacturing hub.

- Direct impact on other countries from local epidemics. China has succeeded in decelerating the spread and some Asian countries, notably Taiwan (just 45 registered cases by March 9) have managed to protect their populations despite proximity and intense travel. It is yet to be proven that control measures will succeed in Western countries with lower tolerance for social control. However, economic damage is already significant, especially in Italy where mass quarantine is introduced. Risks are especially acute in third world countries with weak governments, health systems, but high population densities.

- Second order effects. VIX, the measurement of US stock market volatility has reached the highest point since August 8, 2011, this can harm consumer confidence. Financing opportunities are drying up for higher risk companies. Worsening credit quality can set off vicious cycle of weaker banks and further restrictions on lending. The words “credit crunch” have been already spoken. Oil price crash brings opportunities to importers, but also destabilizes energy sector and important emerging markets.

No one is yet able to make meaningfully certain forecasts about the impact on output, only some components of the rapidly spreading impact. On March 2 OECD stated that the world economy in 2020 will grow by 2.4% in baseline scenario, estimating 0.5pp impact on global growth in contained outbreak scenario and 1.5pp impact of the epidemic spreads through Asia-Pacific and Northern Hemisphere. That is apparently happening now, so the pessimistic scenario or 1.5% growth in 2020 should be increasingly seen as the likely baseline scenario. In this OECD scenario the impact on global growth will peak at 1.8 pp in Q3, it will be a bit lower or ~1.6 pp in both Q2 and Q4.

The Institute of International Finance (IIF, representative of 450 large banks and other financial services providers) updated its forecasts on March 6. IIF reduced its world growth forecast for 2020 from 2.6% to 1.6% (using market exchange rates). China’s growth forecast was downgraded from 5.8 to 4.0%. This assumes V-shaped recovery — decline by 1.0% in Q1, growth by 2.0% in Q2. As Mr. Robin Brooks, the chief economist of IIF recognizes, this is a courageous assumption. Euro area’s growth forecast is revised down from 1.2% to 0.5%, that of the USA from 2.0% to 1.3%. Japan’s economy is expected to shrink by 0.4%, not grow by 0.2%. The fact that forecasts are revised so sharply even when so much is yet unknown about the epidemic gives a pause for thought.

Economic policymakers are not standing idle. The Federal Reserve cut its policy rate by 50 bases points, markets are pricing in additional cuts that would return the USA to zero or near-zero interest rate policy world. It is widely recognized that the answer has to be mostly fiscal. While no one doubts the willingness and ability of the USA to introduce bold measures, it is yet to be seen how euro area will deal with its legal and institutional restraints. Italy has already called to suspend the deficit restraint rules. European Commission has signaled that when assessing the 2020 Stability Programme it “will be mindful of Member States’ need to implement urgent measures to safeguard the wellbeing of citizens and mitigate the negative effects on economic growth of the Coronavirus outbreak”1. We agree that countries should be given extra flexibility to adjust to temporary extraordinary circumstances, but coherent policy framework needs to be preserved.

We think that direct cash transfers from the government to households could be highly appropriate for both containing disease and limiting the negative demand shock. These would address such vulnerabilities as unwillingness of financially vulnerable people to miss work due to income losses that they cannot afford.

The global health drama is a severe disappointment as at the turn of the year it was generally agreed that the world is moving out of the slowdown phase of 2018-2019. This opinion was reflected in a string of stock markets highs. Just after our previous report in September the global outlook initially continued to deteriorate but in November – December a turnaround in “soft” indexes and equity markets started and continued in January – February despite emerging pandemic risks. Manufacturing weakness in developed countries persisted, but so did the divergence with services. Construction remained quite strong, especially in America where housing market strengthened rapidly. There were still some signals of strength in confidence indices in February. For example, euro area’s manufacturing PMI moved close to the “neutral” 50 point line, reaching the highest point in 12 months (49.2). It appears that inventory correction cycle is coming to an end though the low level of inventories could now worsen the effects of supply chain disruptions. The improving mood in manufacturing and financial markets was helped by removal or rather suspension of one of the main sources of stress over the last two years. The first phase US-China trade agreement was concluded. It is reasonable to expect that Donald Trump will try to avoid extra uncertainty that could harm his re-election prospects.

The positive trends of previous months will resume sooner or later, but probably not before H2, 2020 and maybe even not before 2021. When the recovery will start, it will be strong, this pandemic will be a significant, but time-limited shock. The impact on some sectors like air travel and tourism could last longer due to behavioral changes and/or impairment of balance sheets.

There are important messages from financial markets. Soon after our previous report stock indices started a dramatic ascent towards new records. Though equity markets have suffered since mid-February, by March 9 the broadest global stock index had given up only gains since October 10. Further deep declines are nevertheless a realistic possibility. The whole US Treasury yield curve, including 30 year bonds fell below 1% for the first time in history, signaling a very high level of risk aversion. Bloomberg commodity price index is the lowest since August 1986. So, is the relative resilience of the stock market a sign of optimism about an approaching recovery or a sign of desperation about the lack of alternatives as so much of the fixed income world has transformed into fixed losses world, especially in real terms?

Looking at regional aspect, there are signs that divergence between the performance of USA and the rest of the world could widen, both in macro trends and financial markets. While America’s GDP growth slowed down from deficit spending driven acceleration in 2017-2018, the record-breaking expansion remains robust. The recent events could exacerbate this divergence. As a relatively large and self-sufficient economy it will be less affected by global supply chain disruptions. It is not immune, of course. Worries are starting to emerge, for example, composite PMI index in February declined to 49.6 from 53.3 in January.

The virus story is exposing some fundamental weaknesses of euro area. Monetary policy that can react faster, is already very stretched, so there is need for more fiscal policy support, restrained by inflexible rules. While there have been some positive surprises in Europe, the economy remains very fragile. In Italy the recession is unavoidable. There is a high risk of so called “technical recession” in Germany (when GDP falls for two quarters, but in general the economic situation remains favourable).

Germany and Italy continue to teeter on the brink of recession. Japan has continued its history of growth volatility by pushing its economy into sharp decline in Q4 (when GDP fell by 1.6% q/q SA) by another ill-conceived consumption tax rise. Only three G-20 countries grew/are expected to grow faster than the USA in 2018-2020. In emerging markets the big disappointment has been India due to its self-inflicted policy disasters. China showed signs of growth acceleration in late 2019, but outlook there has changed.

Central and Eastern Europe has continued its remarkable bull run, though it is slowing down. Poland, the most important economy here grew by 4.1% in 2019. Expansion remained robust also in other important regional economies — Czechia (2.4%), Hungary (4.9%), Romania (4.1%, IMF estimate from October 2019). For several years these countries benefitted both from transfers of production facilities from Western Europe and strong consumer confidence. However, there are increasing signs that these economies are hitting capacity constraints, the growth will slow down regardless of other issues. Even before the virus story started, IMF predicted slowdowns to 3.3% in Hungary, 3.1% in Poland, 3.5% in Romania in 2020 and further cooling-off in 2021.

Ukraine seems to be recovering, GDP growth accelerated from ~2.5% in 2016-2017 to 3.3% in 2018, it is expected to accelerate from 3.0% from 2020 onwards. Russia’s growth rate continued to fluctuate in a remarkably narrow and also low range and it was expected to continue at 2% rate for several years. The failure of OPEC+ meeting on March 5 has set off a price war in the oil market. Along with price falls in other commodity markets the impact on Russia could be hard. The political leadership had planned for a big growth acceleration push from saved surplus oil income, but now it is under some doubt.

Asia will remain a fast growing region in medium term. For obvious reasons there is a high uncertainty in this region now. While China looks safer by the day, we do not know how the story will play out in countries with weaker governments, health systems and densely populated slums. Moreover, it is increasingly obvious that India’s official GDP numbers are not reliable, the true story of recent years has been quite different. Outlook for

Latin America and Sub-Saharan Africa remains quite poor. Commodity prices are clearly unfavourable and getting worse rapidly.

Baltics entered year 2020 with unusually de-synchronised business cycles. We elaborate on that in country sections, only a brief summary here.

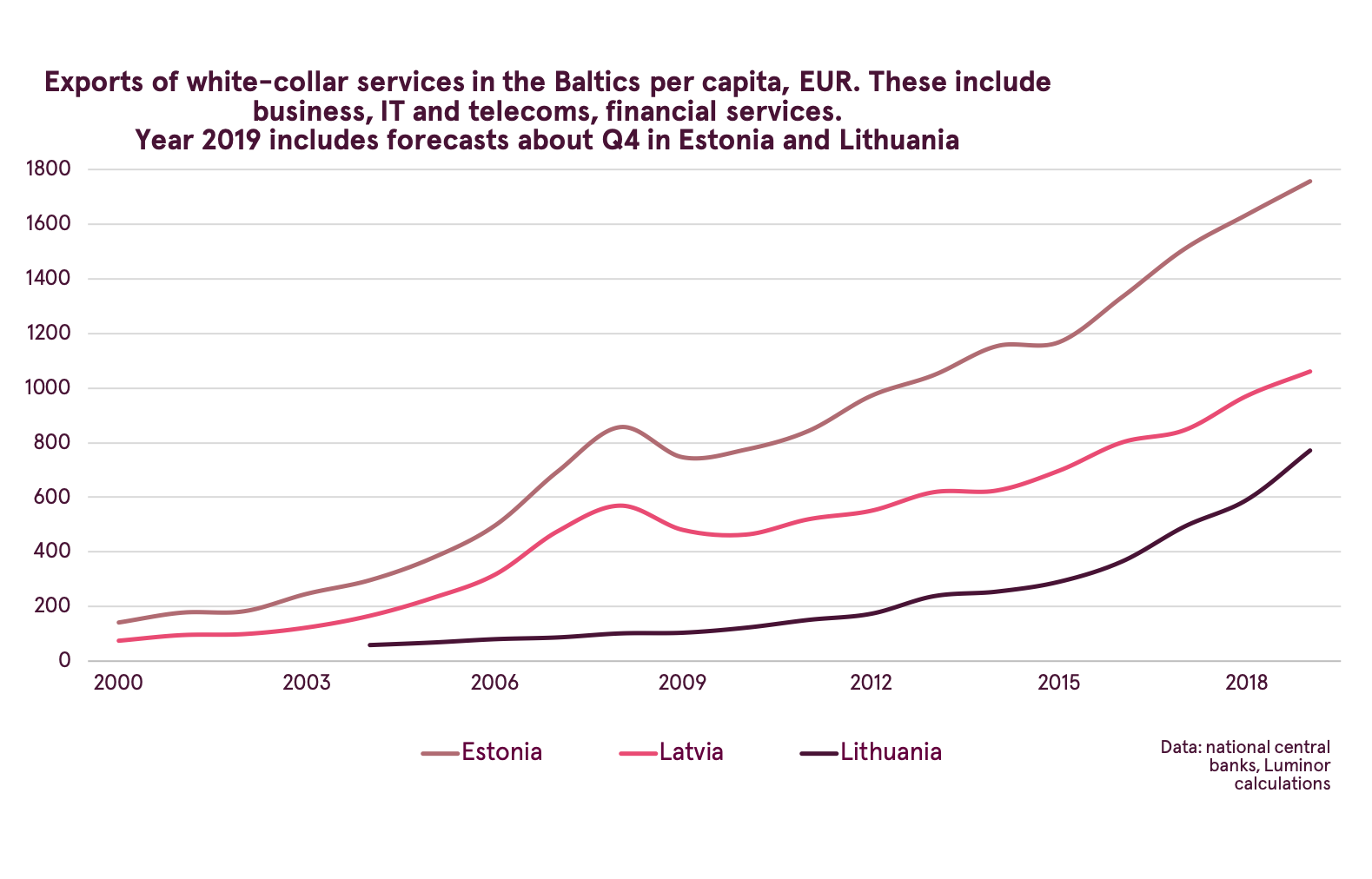

Lithuania is dong surprisingly well. It has succeeded best in attracting manufacturing investment. Its high-value service exports is rising fastest though from a lower base. Its GDP growth rate was almost 4% in 2020 and growth was likely to stay above 3%, now everything is very uncertain. Lithuania has a room for positive upward surprises in following year though it has one specific risk factor — big exposure to changes of EU road transport regulation.

In Latvia growth is more dependent on export markets that weakened sharply in 2019. Plus, unlike in both Estonia and Lithuania where one can observe a strong interplay of real estate development, lending, construction, job growth and consumption, in Latvia the sector is relatively weak and consumer confidence is lowest. For these reasons Latvia was the slowest growing Baltic economy in 2019 and is very likely to be the one also in 2020.

Estonia is gradually slowing down, but from a very fast pace. It is showing its well established strengths. Both its exports of white-collar services per capita and share of high-tech in manufacturing are the highest. Last year information and telecoms service sector grew by staggering 28%, making the biggest single contribution to the GDP growth.

Epidemic risks for the Baltics need to be interpreted with care. There is a significant risk of euro area recession in 2020, but Baltics did reasonably well during two out of three historic euro area downturns. If supply chain disruptions remain persistent and deep, if virus spreads widely here, the story becomes essentially unpredictable. Worries in electronics and pharmaceutical sectors about the security of supplies are already emerging. It is also clear that it would be difficult to resist a general downturn in the world economy. It is already inevitable that most year 2020 will be a lost time for tourism. In this respect Estonia is most vulnerable as tourism revenue per capita here is the highest among Baltic countries. Plus, there are issues of local importance. In all Baltic economies forestry and timber processing play a bigger role than in EU on average, this market largely depends on construction that is cyclically sensitive. The transit of raw materials from the east (mostly Russia) to the west has provided a steady stream of income, this era seems to be ending.

While times are quite troubling, Baltic nations can still look into the future with confidence. Viruses come and go and other countries have shown that this one can be contained. There is a potential for strong recovery in financial markets and upswing in economies which are not experiencing structural impediments or weak balance sheets. Baltics have low government debt and the banking sectors stand on a strong footing. Moreover, the medical systems are robust and well-functioning, staffed with very highly qualified professionals. The situation is unprecedented and unpredictable, which means there is no room for complacency, but also no need to overreact.