A shift to synchronized moderation

Accumulation of risks and elevated uncertainty clouded the zenith of the global business cycle last year. Escalating trade tensions, tighter global monetary conditions and geopolitical strains were among the key sources of uncertainty, which resulted in softer business and consumer expectations, as well as increased market volatility. Markets’ risk-off sentiment hit emerging economies the most, and supported safer assets of the developed world. Emerging Asia, the core engine of the global economic growth, fell in the epicentre of trade disputes and its momentum softened. Those negative risk implications on the real economy were sharpened by idiosyncratic factors (e.g. weather-related effects, or supply-side factors as the new fuel emission standards in Germany, weighing strongly on industry’s performance) and resulted in weaker global macroeconomic pulse at the second half of 2018.

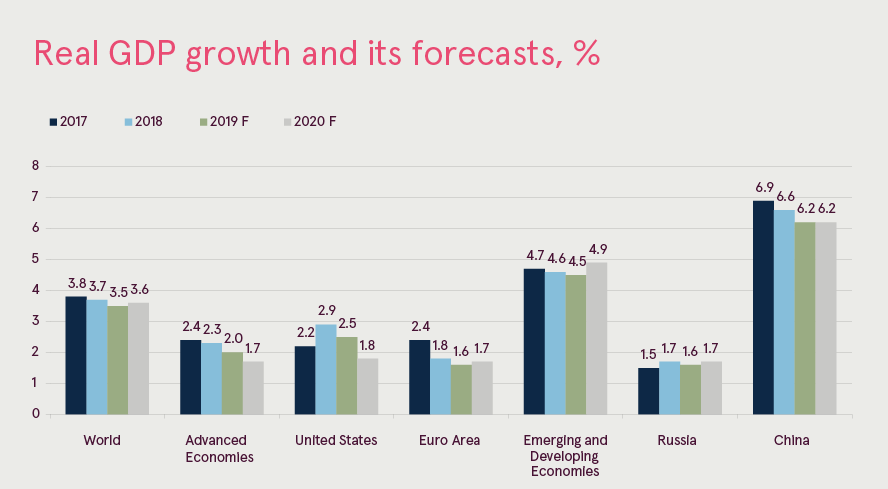

Considering all that, IMF in its January World Economic Outlook pencilled global economy to grow at 3.5% in 2019 and 3.6% in 2020, i.e. 0.2 and 0.1 percentage points below last October’s forecasts. The rationale behind the gloomier global economic projections lies in a range of triggers encompassing weakness in the core euro area economies, toxic mix of populism and fiscal imbalances in Italy, persisting Brexit saga with chronic elevated uncertainty and corporate reshuffling trailing along, and, cherry on top, slowing Chinese economy despite all recent fiscal and monetary efforts fighting this downward path.

Source: International Monetary Fund, Luminor

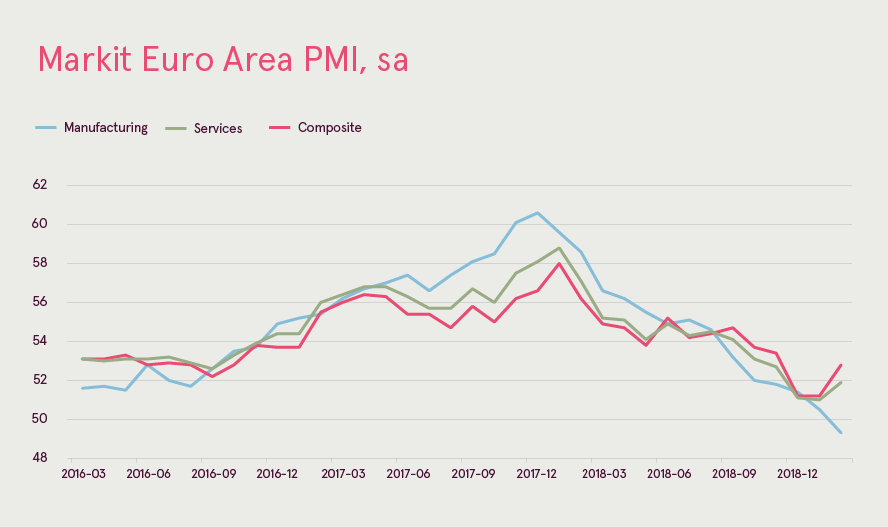

However, at this point we notice monetary policy strategists considering stepping in once again. Despite relatively strong economic and labour market performance in the US, the Fed has started the year sending dovish signals. Elevated markets volatility, trade tensions, dollar appreciation, capital flight from Emerging Markets, high debt levels have been the core source of macro prudential concern and threats to global financial stability, dictating the need for more delicate monetary navigation. The FOMC members, according to the January FOMC Meeting Minutes, questioned the necessity of additional monetary tightening through hiking interest rates. Moreover, more and more FOMC members are in favour of ending the reduction of balance sheet already this year. In the meantime, the economic fatigue on this side of the Atlantic demands pulling out supportive monetary remedies once again. The ECB slashed the euro area’s economic growth forecast by the largest margin since the European debt crisis – now the Bank expects the region to slither at a meagre 1.1% this year instead of earlier forecast 1.7%. Inflation outlook was also worsened from 1.6% to 1.2%. Such a gloomy growth and inflationary projections together with ample liquidity measures conveyed a strong signal that the ECB will continue highly accommodative monetary policy. At the beginning of March the ECB Governing Council decided to keep interest rates at current levels at least until the end of 2019 and unveiled fresh offer of favourable long-term refinancing to the region’s banks starting in September, 2019. The euro area’s economy continues to need monetary support as well as structural reforms to boost growth.

Source: Bloomberg, Luminor

Chinese economy started on a strong footing in 2018, growing by 6.8%. However, softening external demand, local liquidity squeezes within riskier market segments, as well as tariff slaps resulting from the trade dispute with the US escalation put a dampen on growth. As a result, China finished the year growing at 6.4% y/y in 2018Q4, the slowest since the Great Recession. Moreover, it is expected to proceed losing momentum also in 2019 (i.e., 6.2%, according to IMF January WEO, 2019). The Prime Minister L. Keqiang also lowered the target for the country’s GDP growth from 6.5% for 2019 to the corridor of 6-6.5% indicating the possibility of slowest economic expansion in 30 years. This path is already paved by strikingly poor foreign trade readings in February. Slump in Chinese imports points at a deteriorating business and consumer confidence and lost momentum in the domestic demand, while US-China trade tensions sank Chinese exports by 21% y/y. However, the tariff suspension at the beginning of March and the increasing odds of a more lasting trade agreement with the US let China hope for some respite.

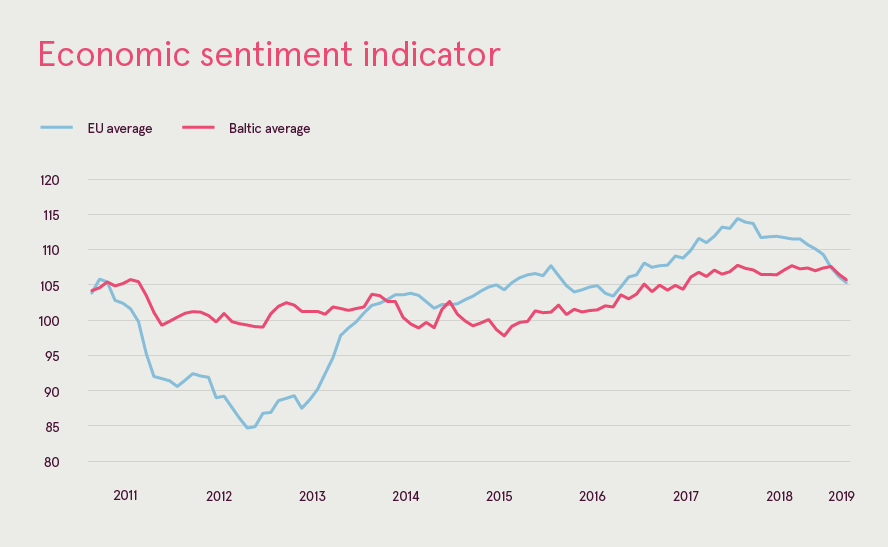

As the economic cycle matures, investments into new growth are increasingly crucial for sustaining the speed of recovery in the euro area including the Baltic countries. The Baltic States are going to face weaker external demand, elevated uncertainty and market volatility. Despite a solid underlying demand trend this may weigh on export confidence, orders and could potentially dampen investments appetite. However, we believe the Baltic open economies will continue recovery at moderating but still robust cruising speed underpinned by solid domestic demand and somewhat slower expansion in the key export markets, the Euro area and Nordic countries.

The Baltics Outlook: An anchor of stability

Baltic economies demonstrate surprising resilience to an ongoing slowdown in global economy and increased geopolitical uncertainties. Contrary to an overall trend in the EU, economic growth in all three Baltic States accelerated in end-2018 and remained well above the EU average. Solid economic sentiment suggest that similar performance can be expected in 2019. Longer-term growth prospects are also brightening due to improving demographic outlook and rising productivity-enhancing investments. Baltic region may have already reached or is about to reach a pivotal point in transforming itself from labour donor to labour magnet, which would increase growth potential and alleviate pressures on social security system.

We reiterate our call made last autumn that downbeat estimates of the region’s long-term growth potential are often being made based on overly-pessimistic demographic and employment outlook assumptions. We proved to be right as employment growth in 2018 was substantially faster than consensus forecasts, while international migration deficits all but vanished in Latvia and Lithuania and remained in positive territory for the fourth year in a row in Estonia. Consequently, vicious cycle of emigration may be transforming into a virtuous cycle of immigration (and re-emigration), which could give a sizeable boost to Baltic economies and cool down overheating labour markets.

Excessive wage growth still remains the key risk as all three Baltic States ranks top-3 in the euro area by nominal unit labour cost growth. However, easing inflationary pressures suggest that a vicious price-wage spiral is losing its velocity. Price convergence with the euro area fell from an alarming 2-3 p.p. in 2017 to a more sustainable levels of 1 p.p. and is expected to remain close to this range in the upcoming years. Moreover, following dismal performance in 2015-2016, productivity growth accelerated and caught-up with wage growth. Consequently, wage growth no longer erodes international competitiveness. Wage convergence with the EU average must continue if Baltics want to attract and retain not only physical, but also human capital.

Baltic economies have no discernible internal or external imbalances: public and private debt levels are exceptionally low and there are no credit nor inflationary bubbles. Belt-tightening policies implemented during the post-crisis period transformed Baltic States from one of the most vulnerable to one of the most resilient regions in the EU. Yet export-driven recovery also made them increasingly open economies, dependent on the health of and access to external markets. An ongoing trade and sanctions war with Russia as well as emerging market weakness also made them increasingly dependent on the EU, hence economic performance of the Baltic States to a large extent will depend on economic health of the EU. In this context, Brexit poses a real, but limited challenge as Britain is among top-10 export destinations. Yet, even in hard Brexit scenario the effect is expected to be limited to no more than 0.5% of GDP.

We expect economic growth to remain robust and broad-based with private consumption, investments and exports all making a positive and fair contribution. Export growth is expected to moderate, but increasing usage of EU-funds will act as a mitigator. Longer-term growth potential will very much depend on how successful Baltic states will be in implementing productivity-enhancing reforms, which would facilitate an ongoing income convergence with the West and transform the Baltics from labour donors to labour magnets.