Overview

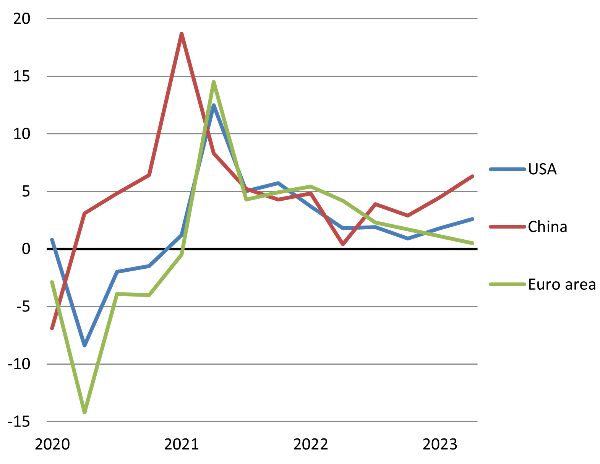

At the time of writing the external conditions for Baltic economies are less favourable than they were during our previous report in March.

Since our last global macro report in mid-March, there have been important positive developments. Most notably, US economic performance has been remarkably strong, largely driven by state promoted manufacturing investment boom as well as AI-driven strong though very narrow stock market euphoria.

Euro area performance has been weaker, but at least it has avoided a long-predicted recession so far, in Q2 economy grew by 0.3% q/q after stagnating in Q1. IMF global growth forecast revision in July was slightly upward, updating global growth forecast by 0.2pp in 2023 and leaving it unchanged in 2024. Euro area’s forecasts were improved by 0.5pp in both years.

However, at the time of writing global growth prospects are worsening rapidly, lead by China and euro area. The leading indicators for euro area are signaling with full force that it is slipping into recession. While China remains relatively strong “on paper”, detailed data are harder and harder to reconcile with GDP numbers that are probably determined by political decisions, not “natural” growth. USA is still relatively strong, but “soft” or future-looking indicators show signs of trouble and real estate sector might yet suffer from interest rate increases in a big way.

Chart. Annual GDP growth in quarters – world, USA, euro area, China.

Euro area and USA

Euro area is already in manufacturing recession and overall recession is looking increasingly likely. The economy still feels the weight of energy price shock. While that is gradually passing away, the impact of interest rate increases is mounting rapidly. Construction and real estate sectors are under big squeeze. Effects of rate increases on investment is compounding the post-pandemic swing away from merchandise demand. Together with the slowdown of Chinese demand of investment goods they are likely causing an outright contraction in German economy this year. Southern European countries still benefit from the recovery of tourism, but there is a question - how long they can hold out against the weakness in the Northern “core”.

The US economy is still going strong, “nowcasts” or measurements of growth momentum are showing annualised pace of up to 6%. It is being supported by its inherent and growing technological supremacy, insouciance about public debt and putting to use of extra household savings. Unlike in Europe, hard data or direct measurements of activity (production, sales) are still strong in the US, but soft indicators are starting to go the way of the “old” continent, with the most recent PMI index barely above the “neutral” 50 point line. The biggest question marks are about the continuing strength of consumer spending as savings levels have almost returned to trend. Rising interest rates have so far little affected the housing construction as the prospect of higher refinancing costs for movers has “frozen” the existing home market. However, the worst housing affordability in more than a generation, consequence of both high prices and high interest rates means that something will have to give in – either rates or house prices. Besides, situation in commercial real estate is worrying, as office vacancies remain far above pre-pandemic level.

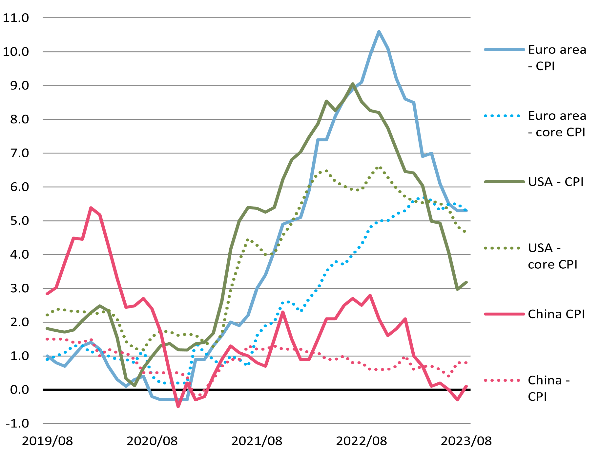

Inflation and monetary policy across the Atlantic

The most important question about the near and medium-term future of the global economy is that of monetary policy in the US and euro area that is inextricably linked to the persistence of inflation. While the headline inflation has been pulled down by a correction of global commodity prices, core inflation is still above the target in the USA and it unclear whether it has begun a sustainable descent in Europe. US performance so far is relatively favourable also in this area largely due to relatively moderate production cost rises in the last couple of years – its industry didn’t suffer from disastrous increases of natural gas and electricity prices. In Europe inflation penetrated deeper into production processes, producers had to reflect this in sales prices and now are holding on these gains while regional energy prices are already much closer to the low-price plateau of the “times of peace” until 2020 than the highest points in 2022.

Chart. Annual inflation in the USA and euro area – headline, core, goods, services.

Even if goods producing sectors are forced to give up their extra margins gradually, inflationary outlook on the both sides of the Atlantic is clouded by the interplay of strong wage rises and service inflation. Month-on-month service inflation in euro area has fluctuated at ca 0,8% in last four months, pushing annual measurement to 5,6% in July from 4,4% in December last year. There are two ways to look at this. One – calm down, nobody expects price level to revert to the previous trend, so it is legitimate that workers enjoy faster wage increases for a while. Due to the service sector cost structure this shows up in prices, but things will calm down as deepening overall economic weakness cools the labour market. Another story – there is a risk that wage and price spiral will go on as rising service inflation will signal workers that they need to keep up their wage demands. They will succeed at least for a while as unemployment levels are at or near historic lows. They might stay there even during a moderate recession as demographic changes tighten labour market.

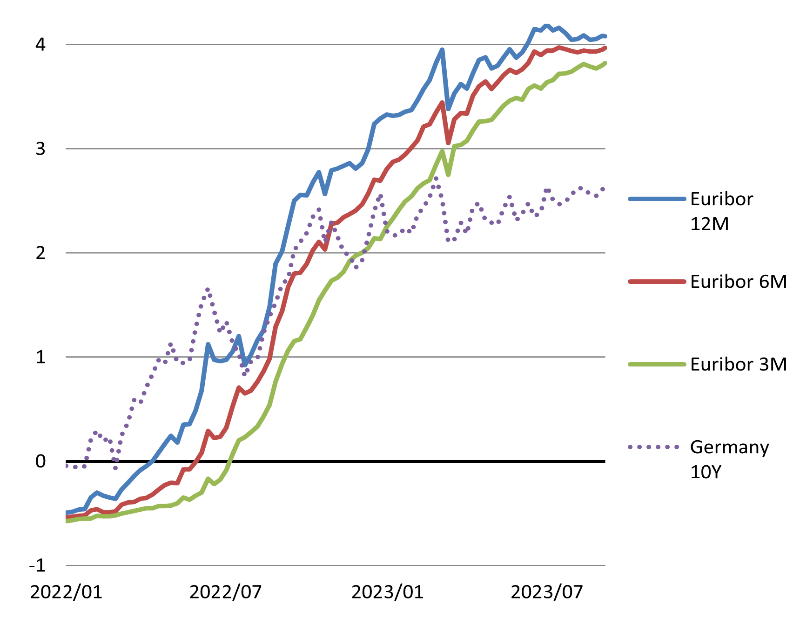

Chart. Real interest rates in USA and euro area. Maybe also China, Japan?

Business cycle dynamics, highlighted by declining soft indicators might justify ECB interest rate decreases already at the end of 2023. In our opinion, ECB will not change its mind so fast. Partly this is for reasons of institutional prestige, rapid change of policy might look like an admission of mistake, also – supporters of hard money policy feel like their views have been disregarded for a long time. Also – there are genuine risks of letting up anti-inflation fight too early and paying the consequences later.

ECB made hawkish errors in 2008 and 2011, after a moment of hesitation, it then went full-heartedly into “whatever it takes” dovish style mode later. We expect ECB rate reductions in 2024 – gradually in H1, rapidly in H2 as economic situation and possibly even southern European government bond market tremors will leave it with little choice.

In the USA the inflationary picture has improved faster than in the euro area, but there are more important questions about the ability to get it back to the 2% target sustainably. The problem has both short-term component (labour market is exceptionally strong) and long-term component (fiscal policies are unsustainable). So a further divergence of interest paths in USA and euro area starting from 2024 appear likely.

China

The biggest disappointment of 2023 has been China where the expected post-Covid bounce dissipated. Annual manufacturing and retail growth rates are trending towards zero and the economy is drifting towards deflation. World’s second biggest economy is bogged down by persistent housing market decline, post-pandemic swing from goods to service demand in export markets, lack of consumer confidence and the increasing weight of government restrictions on economic freedom. Government’s ability to attain its 5% growth target in 2023 is under question and performance is likely to weaken further next year.

There have been many paradigm-shifting headlines about China’s economy recently – about the end of “era”, “miracle” etc. There is no doubt that country’s growth prospects have weakened, but it is also important not to give in to rhetorical flair. China is still moving up the global value chains, the enormous concentrations of smart people and technologies in its major cities provide opportunities for creativity and increasing returns of scale effects that will continue to surprise the world. Its macro-level problems seem manageable in the short run – there is a scope for action on both monetary and fiscal front. Unfortunately, top leadership seems to be obsessed with preoccupations of prestige and geopolitics. The concentration of power in a single leader has corrupted the decision-making process that previously combined authoritarianism and intellectual flexibility in a unique way and built the path for country’s previous successes. This unfortunate development could yet lead to the fulfillment of the worst specifically imaginable global macro risk (grey swan) – dangerous escalation of rivalry between China and the USA.

Other regions

While Scandinavian countries (Denmark, Sweden, Norway) play relatively little role in the global economy, events there currently have a lot of impact on the Baltics, especially Estonia. The Swedish housing boom has ended, predictably, but that does not alleviate the consequences for Baltic exporters, compounding the effects of global timber price declines.

Developments in the rest of the world currently are of secondary importance to the global macro outlook. Japan has had some success in its fight against deflation, but it is unlikely to regain much of its earlier dynamics as the decline of labour force grinds on. India is now the undisputed leader among large economies in terms of growth, but its global weight is still limited and its direct impact on the Baltics – insignificant. Economies of commodity dominated regions show mostly lacklustre growth, with the exception of the Persian Gulf region. In Africa and Latin America the perennial stories of political instability and state disfunction are garnering lots of attention, most notably, in Ecuador, Sudan and Niger. The combination of relatively high/low prices for energy/non-energy commodities does not help as it concentrates incomes in a small group of developing countries.

Global forecasts and assumptions

Taking into account what we wrote above, we believe that euro area growth forecast of the IMF for this year (0.9%) is slightly, but for the next year (1.5%) – significantly on the optimistic side. On the other hand, there is a chance for cyclical recovery in 2025. The estimate of US performance looks solid, with a note that in 2023 (IMF forecast: 1.8% growth) the economy might overperform, though not necessarily at the expense of the following year (1.0%). Thus, the post-pandemic slowdown in rich countries might be more pronounced than IMF thinks (1.5% and 1.4% forecasts for 2023 and 2024 respectively).

We assume that oil prices will remain roughly at current level (between 70-100 dollars for barrel) in the review period. Forecasts of oil appreciation, very popular among financial institutions, have apparently been undermined, among others, by housing market weakness in China, country that famously consumes or at least recently consumed 50-60% of such energy devouring materials as cement, steel, alumina and several other key metals. More pronounced cyclical weakness of the global economy is likely to keep oil prices in check, later in this decade the spread of electrical propulsion technology will start to impact the market in a big way. OPEC+ is keeping a continuous eye on the price developments and is not interested in much lower prices, whereas US and Australia seem to be happy with the current price level. Russia is selling oil to India and other countries and therefore there is no global shortage of oil.

Regional (European) markets for gas and electricity have been an enormously important factor for the Baltic economies. Markets say that the coming winter will bring another price surge, but much smaller than the previous one (for example, gas price for October supplies is EUR 33 at the time of writing, for February - EUR 52). We do not dispute this - while achievements in gas demand and supply differentiation have been remarkable, tightness of supply still could be an issue, depending on weather. Anyway, as the gas prices by some of the leading Baltic utilities are already fixed, this will do less harm to the Baltic disinflationary trends very much during this winter.